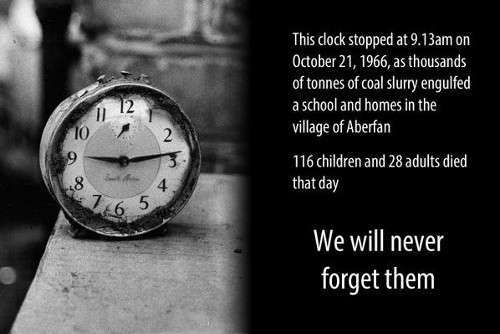

Aberfan remembered

October 21st, 2016

“Blame for the disaster rests upon the National Coal Board” – Inquiry

“Chairman . . .

Could anybody before Tip 7 started — not necessarily a surveyor or an engineer or anything of that kind — could I walking up that mountainside before Tip 7 began fail firstly to see that there was a stream on the land which later became covered by Tip 7? If I used my eyes at all, could I possibly fail to see it?

A. – You could not fail to see it, my lord, no.

Q. – What about the spring you have been referring to? Could a lawyer, with no knowledge of these expert matters at all, taking a country walk up that mountainside, fail to see the place of the spring you have spoken of, or (if the weather was dry) that there was a place where in wetter weather a spring probably ran — could you fail to see that?

A. – He could not fail to see it, my lord, no.

Q. – Those are the stream and the spring, we understand, you tell us later on were covered by Tip 7?

A. – Yes, my lord.”

Paragraph 98 – Evidence of the slinger, Mr. D. B. Jones

What exactly happened?

A coal tip, extended over water sources, slid down a hillside into a junior school and demolished several houses killing 144 people in its path.

“The slips of [1939 – Ed] 1944, 1963, and 1966 resulted from the fundamental mistake of tipping over surface streams and springs or seepages emanating from permeable strata forming the sloping hillsides without taking any preliminary drainage measures.” Link

Why did it happen?

Because a report from 1927 and precedents stretching back to 1939 were ignored by all those responsible for the production of coal, including a major slide by the disaster tip itself in 1963.

“But the Aberfan disaster is a terrifying tale of bungling ineptitude by many men charged with tasks for which they were totally unfitted, of failure to heed clear warnings, and of total lack of direction from above.

Not villains, but decent men, led astray by foolishness or by ignorance or by both in combination, are responsible for what happened at Aberfan.

That, in all conscience, is a burden heavy enough for them to have to bear without the additional brand of villainy.” – Paragraph 47

Need it have happened?

“. . . Not only was nothing done to prevent any further failure, but the very course of action most likely to give rise to a further slide was immediately embarked upon — that is, tipping into the hole left by the slide and reconstituting the tip as far as possible into its pre-failure condition”. – Paragraph 133

“Indeed, between the major slip of November, 1963 and the disaster the point of the tip advanced no more than about 8 feet in all, while its toe was advancing ever downwards and across the mountainside.” – Paragraph 158 last sentence.

“But the evidence strongly points to their having entertained for some weeks before the disaster doubts about stability — and they had ample grounds for entertaining such doubts. Even during those last weeks tragedy could have been averted had the Manager then alerted higher authority.”

What lessons are to be learned from what happened at Aberfan?

Don’t tip coal waste on hillsides, over water sources.

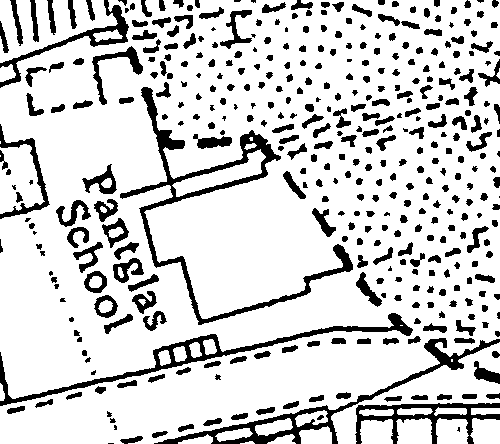

Cilfynydd 1939 slide clearly visible in this 1945 photograph

This incident alone, a few miles south of Aberfan, ought to have been sufficient to prevent tipping above Aberfan but it was forgotten or ignored despite its magnitude. Never mind the subsequent slides above Aberfan itself in 1944 at Tip 4 and 1963 at Tip 7 followed by the NCB continuing to tip into the hole created by the 1963 slide until it slid again, and for the last time, in 1966.

Findings:

I. Blame for the disaster rests upon the National Coal Board (Paragraph 74). This blame is shared (though in varying degrees) among the National Coal Board headquarters, the South Western Divisional Board, and certain individuals (Paragraph 188).

II. There was a total absence of tipping policy and this was the basic cause of the disaster. In this respect, however, the National Coal Board were following in the footsteps of their predecessors. They were not guided either by Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Mines and Quarries or by legislation (Paragraph 66).

III. There is no legislation dealing with the safety of tips in force in this or any country, except in part of West Germany and in South Africa (Paragraph 70).

IV. The legal liability of the National Coal Board to pay compensation for the personal injuries (fatal or otherwise) and damage to property is incontestable and uncontested (Paragraph 74).

http://www.dmm.org.uk/ukreport/553-01.htm

On reading the report one learns that two large water mains in the disused Glamorgan canal formerly linking Merthyr Tydfil with Cardiff were broken by the tip slide and added to the disaster for some time before they were turned off. I presumed at first this was owing to poor communication but have found out since then that it was simply a fact of life in dealing with large water mains as well described by Tony Austin in his book about the disaster.

“One main, 31 inches in diameter, belonged to the Taf Fechan Water Board, and contributed 3-3/4 million gallons of water a day to suburban Cardiff and large amounts elsewhere as well as to Aberfan itself; a 27 inch main was that of Cardiff City Corporation, serving the city with some eleven million gallons a day.

Between them the mains that were broken were supplying Cardiff with two-thirds of its water supply. The tip ripped 150 yards out of each.

By chance Mr Fred Marshall, one of the Taf Fechan engineers was in Merthyr Town Hall when the news came through. He returned to the board offices across the road where the divisional engineer, Mr Colin Jones, called a gang from the reservoir in the Brecon Beacons to the office and then telephoned Cardiff Citys’ undertaking. Thus both authorities knew of the situation well before urgent messages started arriving from the fire brigade and police.

A water main cannot be turned off quickly. The very method employed, to manually lower a gate across the pipe, is slow. Cardiff’s main needed 200 turns of a highly geared mechanism to lower the gate; the bigger Taf Fechan main required 320 turns.

Nor can a gate be shut by one man – two, at least, are required and mains of this size take an hour to close. In itself this is a safety precaution. The water flows at pressure; if it were possible to bring it to a sudden stop pressure waves would build up and burst the pipe above the point of closure.

Cardiff, communicating by a radio system which the Taf Fechan board did not have, sent three men from Cardiff to Merthyr Tydfil to turn off their main at the nearest valve to the fracture, some four and a half miles up pipe from Aberfan.

They closed it down by 10.45 after which the water in the main had to drain away. At the same time the valves allowing water into the main from the reservoirs were shut.

Although nearer, the Taf Fechan board faced a more complicated situation. Jones and Marshall went to Aberfan, found that not only was their main torn and buried under the avalanche, but that the Aberfan valve and branch main serving the village had gone too.

They returned to Merthyr Tydfil to meet the gang from the reservoir and went to the nearest valve, at Abercanaid, two miles up main from the break. They closed it about the same time as the Cardiff engineers closed theirs – 10.45.

Now Jones and Marshall had another main to shut down: four years previously the Taf Fechan board laid a 24 inch main to Cardiff on the opposite side of the valley. The new main was cross linked with the fractured main two miles to the south; the result was that the 24 inch main was feeding water back up the 31 inch pipe and still flooding out at Aberfan. They raced to the down main and working remarkably quickly had it shut at 11.30.

That valve was again two miles away, and two more miles of pipe had to drain before the flow finally finished at about midday. Between two and three million gallons of water had been added to that already issuing from the tip.”

Aberfan – Tony Austin – pp39-40

Reference to the burst water mains is made in the documentary entitled “Surviving Aberfan“, including film of water running over steps and down the streets.

Click image for effect of tip on the village

Taken from page 29 of the Report of the Tribunal

The Inquiry report itself is so good, so eloquent, so unstinting in its research and conclusions that if you can find the time to absorb 165 pages of diagrams and text, it alone is sufficient to understand the facts.

If however you desire a faster introduction to the subject then may I recommend the more recent and much shorter though no less acerbic paper by Professor Ian Maclean entitled Aberfan – no end of a lesson or the excellent Tipping point by Ted Nield

Bibliography

The inquiry report

http://www.mineaccidents.com.au/uploads/aberfan-report-original.pdf

and here to order:-

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C598235

An online version of the inquiry report

http://www.dmm.org.uk/ukreport/553-01.htm

The Parliamentary debate

http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1967/oct/26/aberfan-disaster

A modern look at the disaster by Professor Ian MacLean

http://www.historyandpolicy.org/policy-papers/papers/aberfan-no-end-of-a-lesson

A civil engineers view of what happened

https://www.ice.org.uk/eventarchive/whatever-happened-to-aberfan-cardiff

Aberfan by Tony Austin

A book published a year later about which I will have more to say in due course.

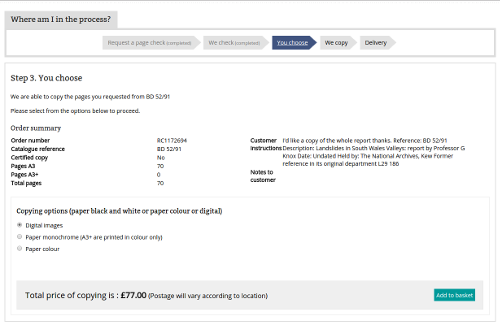

Landslides in South Wales Valleys:-

Report by Professor G Knox – dated 1927

http://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C598172

I enquired about purchasing a copy of this report. They want £77 for it and that was after a “page check” fee of £8.24 which I had to pay to reach stage two.

Web resources

Arson at Capel Aberfan in 2015

http://www.walesonline.co.uk/news/local-news/we-make-beautiful-place-pastor-9680716